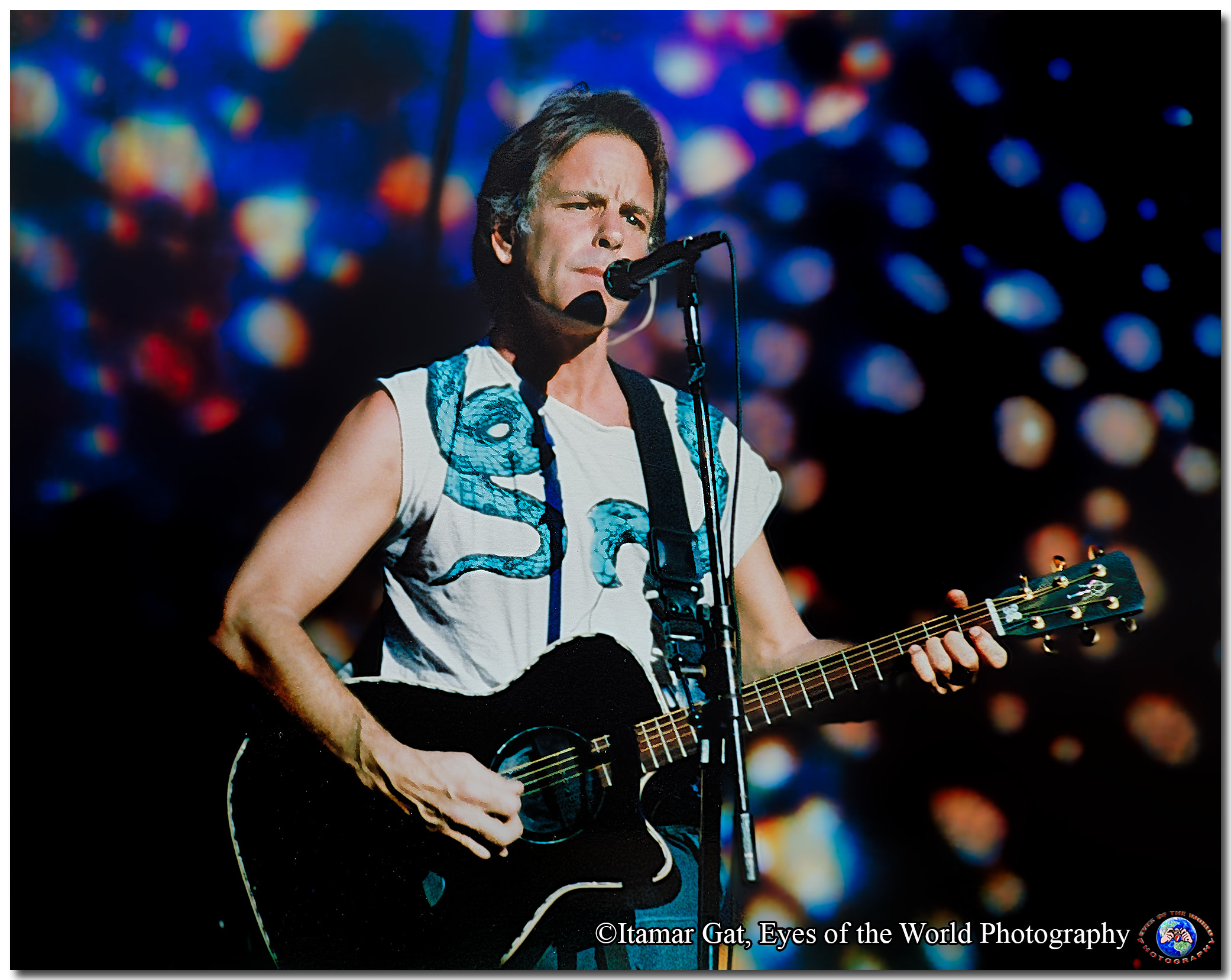

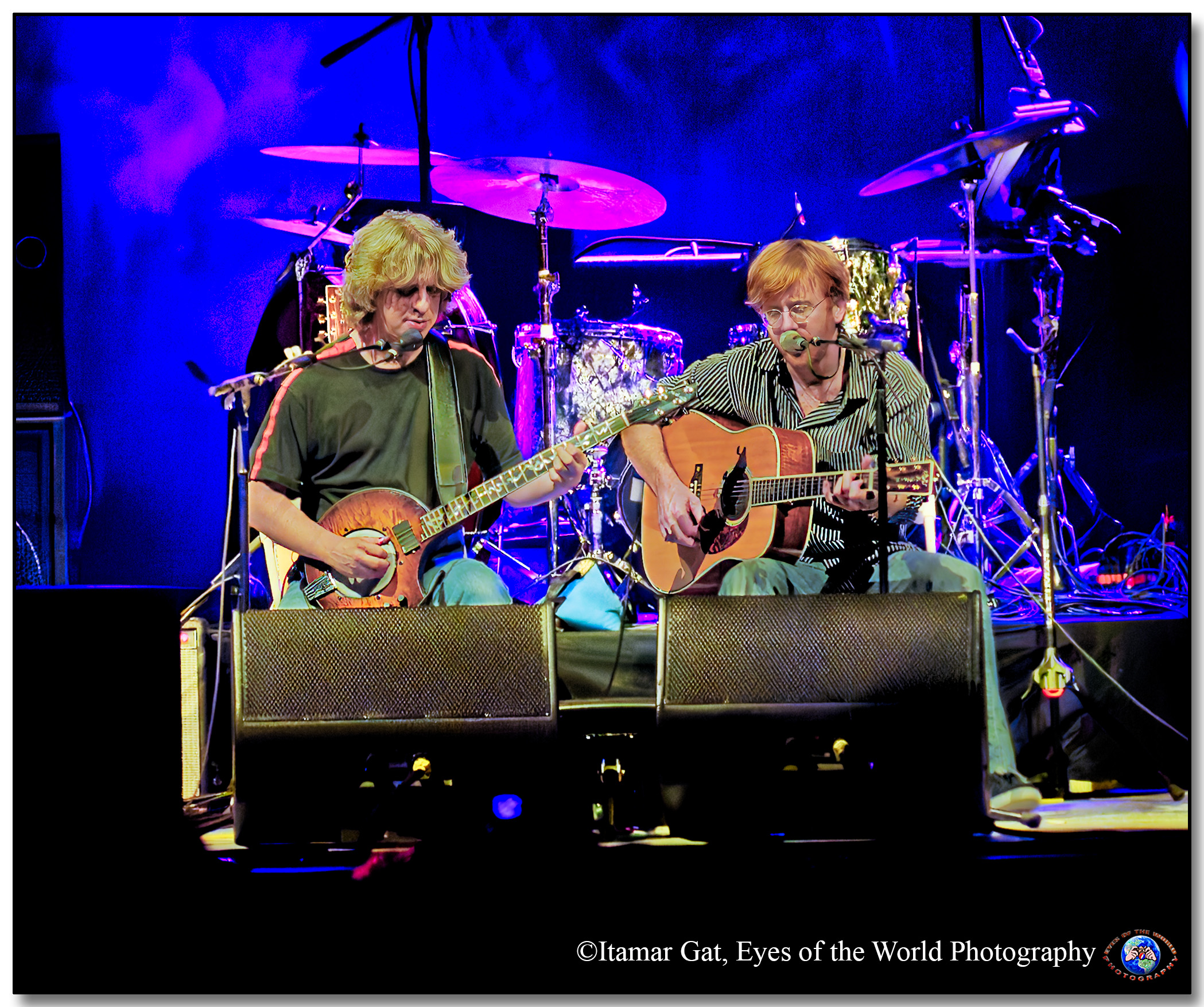

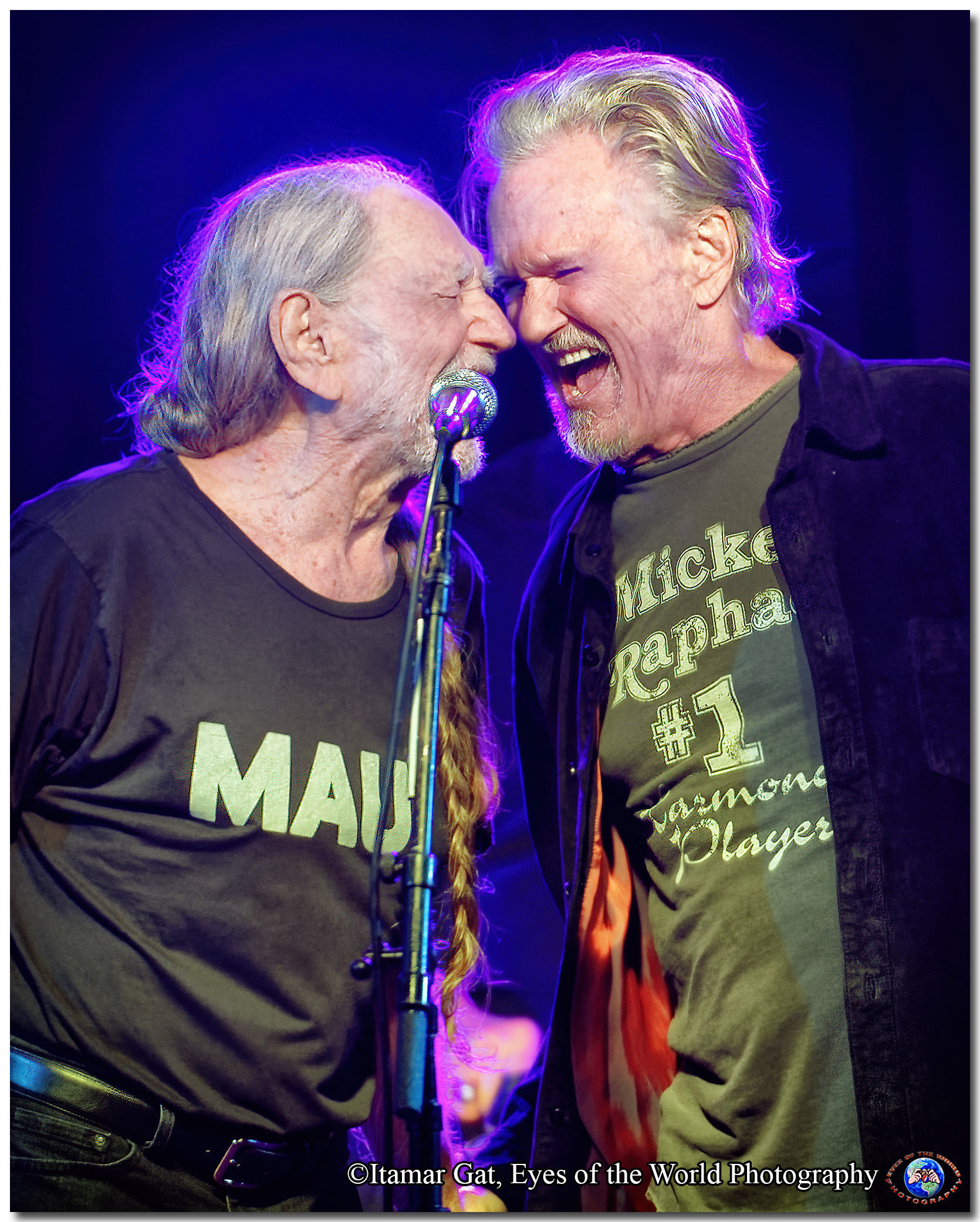

There are photographers who capture concerts, and then there are photographers who capture the spirit of live music. Itamar Gat belongs to the latter. For decades, he has been a visual historian of the jam band festival scene, photographing artists whose music thrives on improvisation, emotion, and connection. His images don’t just document performances, they bring the human factor into them. He channels light, movement, and sound into something almost musical in itself. I had the chance to speak with Itamar about how he got his start, stories of the past, what keeps him inspired, and what advice he has for those hoping to join the fray in the pit, behind the lens. What follows are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Midwest Riff Review (MRR): Itamar, you and I met a couple of years back while working at Dark Star Jubilee and I remember distinctly some of the fascinating stories you told about opportunities you’ve had to photograph artists, shows, and festivals. Those reading this will be equally interested to hear how you first got into concert photography, what drew you to it?

Itamar Gat (IG): I mean, I was always a music lover and specifically a deadhead, especially the times I lived in California. In the early to mid 90’s the scene was incredible. I had a passion for photography, and by the time I moved to California I already fancied myself a photographer even though I didn’t have a ton of experience in the music industry. During that time, especially in the Bay Area, there was a ton of music and it was pretty loose. I mean, nobody bothered you if you had a camera in the crowd. At the time, I had a Minolta. It was a nice camera with auto focus, but not a bunch of quality lenses and so it just looked like a Joe Schmo camera and nobody bothered me taking pictures in the crowd. Eventually I decided to test the waters and walk up closer with a questionable press ID I had and found that if I flashed it fast and kept walking I found myself in front of the stage. From there it took a life of its own. I was able to show a couple of my images to the people in the Grateful Dead community and the Rex Foundation (A charitable organization founded by members of the Grateful Dead providing grants to grassroots organizations working in the arts, sciences, and education).

MRR: So were you shooting concerts for the Dead?

IG: Not necessarily for the Dead. At the time, there was always a group of photographers in the San Francisco area shooting all their concerts like Bob Minkin, Jay Blakesberg, and Susana Millman. They were all very well established already. I was new to the scene and wasn’t getting paid, but I knew some people and was able to get photo passes because people knew me. It was then I started doing work for the Rex Foundation which was a blast and helped me make a name for myself so I could start approaching other promoters and get passes as well as getting paid.

MRR: Wow, that’s amazing. So was there a particular show or performance that you’d consider being your first show as a credentialed photographer?

IG: Um, I’m trying to remember. Thinking about it, the first show I think that I was legitimately shooting was the Grateful Dead at Shoreline in 1994, but I’m not exactly sure. You know in those days, I mean, it seems like every weekend we went to a show of some kind. A lot of Grateful Dead, but other stuff.

MRR: Amazing to imagine for sure. What are some of the other memorable shows from that era that you remember photographing?

IG: Well, the Allman Brothers Band, and right after Jerry passed, there were so many groups of musicians who got together to celebrate Jerry’s life. Arlo Guthrie, Bonnie Raitt, and Stephen Stills, I believe were all in one show in Sacramento that I was photographing. Yeah, it was mostly around the jam music scene and there was a lot of it going on.

MRR: Do you have a particular concert of that era that stands out? A favorite that stands out if you can name one?

IG: Um, I think as far as, let’s put it this way, I think was a collection of musicians on stage in ’96 or ’97, a Further tour involving the remaining members of the Grateful Dead playing with a ton of other musicians at Shoreline Amphitheater that featured just about anybody in the jam band scene at the time. That stands out because of the amount of legends that were on the stage.

MRR: Fans of your work, and those who may just be discovering you, likely know you from your festival photography like Dark Star Jubilee, All Good Now, and 4848. How did you get into festival work?

IG: Really, my festival work didn’t start until the early 2000’s after I moved to Ohio. When I moved, the music scene somewhat died for me as I knew nobody there. I was still flying out west to shoot some of the Rex Foundation shows, but in Ohio I couldn’t get any work. I then came across this guy that was running the 10,000 Lakes Festival in Minnesota and that’s when my festival photography career started. Since then, I’ve really only shot a handful of concerts for bands. It’s now mostly festivals, which for me, first of all, the money is ten times better. It’s extremely hard to make money in this industry as a concert photographer unless you’re a touring band photographer. To just go out there and shoot a show doesn’t really pay a whole lot, if at all.

MRR: So what is it about the festival that started grabbing your interest?

IG: The festival just gives you an opportunity to shoot so much more. I’m not talking about just the musicians playing there. It’s basically a circus that you’re thrown into for 3 days with endless photo opportunities. I just really prefer and enjoy that a whole lot more than shooting a single concert.

MRR: I think you’re right. If you’re shooting a festival as a hired photographer, the access is a whole lot different.

IG: Yes, access is really, really key and you don’t have the same restrictions in the pit or elsewhere that you would likely have at a single show. When you work for the festivals, those restrictions hardly ever exist.

MRR: Let’s talk about style for a minute. Your images have a real distinctive feel to them. The energy you capture in your pictures and the style you’ve created. How would you say you’ve come about your style?

IG: So obviously, the move to digital has really changed a lot. I used to work in my own color dark room processing all my own images which gave me an advantage to a degree, but digital opened up quite a lot. I’m concentrated on the human aspect of the music for the most part. Yeah, I absolutely love the lights, but you’ll see less of these wide, crazy light shots from me compared to other photographers. It’s not that I don’t love to see other photographers doing incredible work with lights, but for me it’s two things really. First, I’m really interested in the human aspect of things. The musicians and the fans. So I like close-ups of the musicians. I like to try and catch interactions between musicians, whether it’s a facial expression or just looking at each other.

The same goes for the crowd, you know, it’s kind of a hunt for me whether I’m standing on stage or in the concert bowl area. I like to find an interesting subject and sometimes just follow them because I think they’re interesting and try to capture a moment they’re experiencing. I like to shoot the crowd with both wide and telephoto. The 200mm especially gives you a little more candid because you can shoot from further away Often, I’ll see somebody interesting and instead of just raising the camera and taking photos, I’ll try to get out in front of them and then look for my photos capturing them in the overall scene.

The other part that contributes to my style is the technical quality of my images I probably over edit, meaning I just spend so much time on my images. I have this obsession with the perfect image. So that’s what I consider to be my style. The human aspect is huge, huge, huge for me.

MRR: Do you have any sort of creative plan in the back of your head going into a festival in terms of what you’re going to try and accomplish?

IG: Yeah, kind of. I always try and get to the festival the day before, especially if it’s a new venue. That gives me some time to figure out what are good spots. I have this picture from the very first All Good Festival I’ve done, probably around 2010 when the festival was in West Virginia. They gave me a golf cart to get around in, and I remember driving all over the venue when the place was deserted and the sun was setting. I was at this observation point seeing the sun setting over the stage, so I knew basically when the sun would be setting over the stage to where I could go back and get some wide shots. I got extremely lucky because I went there to take a photo on the second day I think it was, and completely out of the blue this young woman with a hula hoop came out. It’s one of my favorite photos, and it was just because I planned ahead, you know, I was at the right spot and she just came in unplanned.

So yeah, I do have a general plan, especially if I shoot the same place. It’s hard to come up with new things at a familiar venue so I try to come up with new ideas of things that I might want to capture at that festival that maybe I didn’t at another.

MRR: One question I always like to ask fellow concert photographers to get their unique perspective is, what advice would you give somebody who is trying to break into the scene, whether for a hobby or for a living.

IG: Yes, I would say, it’s very hard to break into this industry to make money so the first thing I would tell anyone, even for beginners is to have a decent portfolio. Approaching a promoter or band and saying, hey, I’ve got a great camera isn’t going to cut it. It’s very important to have a nice portfolio. And then, especially for beginners, I would say, patience is the name of the game when you’re shooting. I see a lot of inexperienced photographers, especially if they’re only getting 15 minutes in the pit to shoot, just shooting like crazy. So my advice, even if you’re limited by time is to explore your surroundings. See where the lights are on stage. If it’s a band you know, you probably know when the big moments in the song are going to be, so be prepared for that. Shoot with intention. A lot of people are just like, oh, I only have 15 minutes, I’d better get a photo of everybody and keep moving from musician to musician with no intention. I suggest you learn your environment, take a couple of minutes to explore it, and shoot with intention. Also, I try to make friends with everybody. I don’t have a sense that I’m competing with other photographers. We’re all made of the same, uh, mold you know. We all like photography, we all like music so we have a lot in common. I see a lot of people that are the opposite. Protecting their secret fishing spot is how I put it. My advice, just make friends. It’ll help you in the future, especially with folks like the security guards and the catering people if you’re working a festival.

MRR: So my last question, if you could be remembered for a single image that defines your work, what would that be? The hula hooper at sunset maybe?

IG: Oh, that was one of my favorites personally from the way everything tied together, but the one picture that probably helped propel my career in this industry is a photo I took of Jerry back in 1994. It was actually of the Jerry Garcia Band at the Ventura County Fairground. It was an outdoor show and Jerry was under the weather so he was wearing this black cape. And, I grabbed a photo of him from the back. He had is back to the crowd, and it was dark, and you could see a teeny bit of the outline of the cape. But basically the photo is the silver hair and the neck of the guitar from the back.

MRR: Oh, wow!

IG: And so, what was interesting about this photo is when I took it, and this was still film, I remember going into the darkroom and I looked at it. I printed a couple of 8×10’s, and the photo wasn’t tack sharp, and I looked at it and I go, eh, and threw it in a box. I remember though coming back on the day Jerry died and started digging through boxes looking for something to hang on the refrigerator. I start going through boxes of prints and this popped out and I started looking at it and realized how ghostly the entire image was because it was a teeny bit out of focus and because there were no faces in it, just everything dark except Jerry’s hair and the guitar neck. I immediately remembered when I was taking that photo and it reminded me of the line of their song, “Like and angel, standing in a shaft of light.” This one really helped me get into the industry. There are 1000’s of great images of Jerry at the time, but this one was somehow different from many that you’ve seen. I’m not saying it’s the best ever taken, but it’s different.

I had the opportunity while working for a newspaper to take photos of a Cleveland billionaire who did a lot of charity work. When I went to his office, he had a huge painting of Jerry Garcia in there and I thought, wow, how interesting. I knew going in that he was a philanthrapist with an art collection so I thought maybe it was just a piece in his collection. After I took a couple of shots of him, I asked him about it and he said, yeah, I’m a huge deadhead and so I told him, oh, I have something interesting for you. So I went home and got the photo and came back to his office and I’ll never forget, he says, “It’s mine,” and asked me to print him a 30×40 which he bought from me. And then he goes, “Hey, I run this music festival in Minnesota, would you be interested in coming and photographing my event. So that’s really what started my career.

MRR: Well, I can’t think of a perfect note to end on! I really appreciate you taking the time to share your experiences and insights, Itamar. This has been a lot of fun and I’m sure the readers will equally enjoy hearing your perspective. Thanks again for chatting today!”

To keep up with everything Itamar has going on, you can connect with him on his website, Facebook, and Instagram, and if you enjoyed this conversation and want to see more interviews with concert photographers who inspire and innovate, let us know who you’d like to hear from next. Drop a comment or message us on social media and stay tuned for the next edition in this series.

Leave a reply to Lindsey McCutchan Cancel reply